ARBITRATION, TRIBUNAL ADJUDICATION AND ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION

ARBITRATION, TRIBUNAL

ADJUDICATION AND

ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION12

12.1 INTRODUCTION

Law is one method of resolving disputes when, as is inevitable, they emerge. All societies have mechanisms for dealing with such problems, but the forms of dispute resolution tend to differ from society to society. In small-scale societies, based on mutual co-operation and interdependency, the means of solving disputes tend to be informal and focus on the need for mutual concessions and compromise to maintain social stability. In some such societies, the whole of the social group may become involved in settling a problem, whereas in others, particular individuals may be recognised as intermediaries, whose function it is to act as a go-between to bring the parties to a mutually recognised solution. The common factor remains the emphasis on solidarity and the need to maintain social cohesion. With social as well as geographical distance, disputes become more difficult to deal with.

It should not be thought that this reference to anthropological material is out of place in a book of this nature. It is sometimes suggested that law itself is a function of the increase in social complexity and the corresponding decrease in social solidarity; the oppositional, adversarial nature of law being seen as a reflection of the atomistic structure of contemporary society. Law as a formal dispute resolution mechanism is seen to emerge because informal mechanisms no longer exist or no longer have the power to deal with the problems that arise in a highly individualistic and competitive society. That is not to suggest that the types of mechanisms mentioned previously do not have their place in our own society: the bulk of family disputes, for example, are resolved through internal informal mechanisms without recourse to legal formality. It is generally recognised, however, that the very form of law makes it inappropriate to deal adequately with certain areas, family matters being the most obvious example. Equally, it is recognised that the formal and rather intimidatory atmosphere of the ordinary courts is not necessarily the most appropriate one in which to decide such matters, even where the dispute cannot be resolved internally. In recognition of this fact, various alternatives have been developed specifically to avoid the perceived shortcomings of the formal structure of law and court procedure.

In its 1999 Consultation Paper, Alternative Dispute Resolution, the Lord Chancellor’s Department (LCD) redefined ‘access to justice’ as meaning:

[W]here people need help there are effective solutions that are proportionate to the issues at stake. In some circumstances, this will involve going to court, but in others, that will not be necessary. For most people most of the time, litigation in the civil courts, and often in tribunals too, should be the method of dispute resolution of last resort.

That extremely useful Consultation Paper also set out the following list of types of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms:

• Arbitration is a procedure whereby both sides to a dispute agree to let a third party, the arbitrator, decide. In some instances, there may be a panel. The arbitrator may be a lawyer or may be an expert in the field of the dispute. He will make a decision according to the law. The arbitrator’s decision, known as an award, is legally binding and can be enforced through the courts.

• Early neutral evaluation is a process in which a neutral professional, commonly a lawyer, hears a summary of each party’s case and gives a non-binding assessment of the merits. This can then be used as a basis for settlement or for further negotiation.

• Expert determination is a process where an independent third party who is an expert in the subject matter is appointed to decide the dispute. The expert’s decision is binding on the parties.

• Mediation is a way of settling disputes in which a third party, known as a mediator, helps both sides to come to an agreement that each considers acceptable. Mediation can be ‘evaluative’, where the mediator gives an assessment of the legal strength of a case, or ‘facilitative’, where the mediator concentrates on assisting the parties to define the issues. When mediation is successful and an agreement is reached, it is written down and forms a legally binding contract unless the parties state otherwise.

• Conciliation is a procedure like mediation but where the third party, the conciliator, takes a more interventionist role in bringing the two parties together and in suggesting possible solutions to help achieve an agreed settlement. The term ‘conciliation’ is gradually falling into disuse and the process is regarded as a form of mediation.

• Med-Arb is a combination of mediation and arbitration where the parties agree to mediate, but if that fails to achieve a settlement, the dispute is referred to arbitration. The same person may act as mediator and arbitrator in this type of arrangement.

• Neutral fact finding is a non-binding procedure used in cases involving complex technical issues. A neutral expert in the subject matter is appointed to investigate the facts of the dispute and make an evaluation of the merits of the case. This can form the basis of a settlement or a starting point for further negotiation.

• Ombudsmen are independent office-holders who investigate and rule on complaints from members of the public about maladministration in government and, in particular, services in both the public and private sectors. Some Ombudsmen use mediation as part of their dispute resolution procedures. The powers of Ombudsmen vary. Most Ombudsmen are able to make recommendations; only a few can make decisions which are enforceable through the courts.

• Utility regulators are watchdogs appointed to oversee the privatised utilities such as water or gas. They handle complaints from customers who are dissatisfied by the way a complaint has been dealt with by their supplier.

While ADR is usually regarded as referring to arbitration and mediation and the operation of the Ombudsman scheme, this chapter will extend this meaning to allow an examination of the role of the various administrative tribunals that exercise so much power in contemporary society.

12.2 MEDIATION AND CONCILIATION

A number of alternatives to court proceedings have already been listed, but the two most common, or certainly the two that most immediately spring to mind when the topic of ADR is raised, are mediation and conciliation, and as a consequence, although distinct, they are dealt with together.

12.2.1 MEDIATION

Mediation is the process whereby a third party acts as the conduit through which two disputing parties communicate and negotiate, in an attempt to reach a common resolution to a problem. The mediator may move between the parties, communicating their opinions without their having to meet, or alternatively the mediator may operate in the presence of the parties, but in either situation the emphasis is on the parties themselves working out a shared agreement as to how the dispute in question is to be settled.

Before the Woolf reforms introduced the three-track system, the small claims process was referred to as mediation, due to its much less formal procedural rules and practices. Although the small claims track is still relatively informal in comparison with the other tracks (see Chapter 5.5 above), the Court Service introduced a distinct and specific mediation process as an alternative to the court-based procedure. This small claims mediation scheme is funded by HMCS and consequently is free to court users who have a defended small claim.

The scheme was assessed positively after a pilot at Manchester County Court, and in 2007 HMCS began to appoint a number of small claims mediators across England and Wales. By June 2008 each of the 23 HMCS Court Areas in England and Wales had an in-house small claims mediator to deal with appropriate cases.

The small claims mediator settles the majority of disputes over the telephone without the need for either party to attend court, consequently reducing time and expense. However, if necessary, face-to-face mediation can be arranged, either on court premises or elsewhere as deemed appropriate. In the event of the parties not being able to reach a settlement at the mediation appointment, the case will be listed for a small claims hearing. As the mediation process is confidential, the judge who deals with the subsequent case in court will not be informed of the content of any discussions at any previous mediation proceedings.

Mediation is also available for higher value claims through the National Mediation Helpline, which, although not free, is much cheaper that making use of lawyers and going to court. Although the Helpline is mainly aimed at fast- and multi-track disputes (i.e. above £5,000), it can also deal with small claims.

The fees for using the National Mediation Hotline are:

| Amount claimed | Fees (per party) | Length of session | Extra hours (per party) |

| £5,000 or less* | £50 + VAT | 1 hour | £50 + VAT |

| £100 + VAT | Up to 2 hours | ||

| £5,000–£15,000 | £300 + VAT | Up to 3 hours | £85 + VAT |

| £15,000–£50,000** | £425 + VAT | Up to 4 hours | £95 + VAT |

The way in which mediation operates will become clear from the cases considered below. General information about the operation of mediation may be found at the National Mediation Helpline (www.nationalmediationhelpline.com) which is in itself an indication of the current importance of ADR as a means of resolving disputes. Equally helpful, with excellent flow diagrams on the relationship of ADR and court processes, is the Civil Court Mediation Service Manual produced by the Judicial Studies Board, which is available at www.jsboard.co.uk/downloads/civil_court_mediation_service_manual_v3_mar09.pdf

12.2.2 MEDIATION IN DIVORCE

Mediation has an important part to play in family matters, where it is felt that the adversarial approach of the traditional legal system has tended to emphasise, if not increase, existing differences of view between individuals and has not been conducive to amicable settlements. Thus, in divorce cases, mediation has traditionally been used to enable the parties themselves to work out an agreed settlement rather than having one imposed upon them by the courts.

This emphasis on mediation was strengthened in the Family Law Act 1996 but it is important to realise that there are potential problems with mediation. The assumption that the parties freely negotiate the terms of their final agreement in a less than hostile manner may be deeply flawed, to the extent that it assumes equality of bargaining power and knowledge between the parties to the negotiation. Mediation may well ease pain, but unless the mediation procedure is carefully and critically monitored it may gloss over and perpetuate a previously exploitative relationship, allowing the more powerful participant to manipulate and dominate the more vulnerable and force an inequitable agreement. Establishing entitlements on the basis of clear legal advice may be preferable to apparently negotiating those entitlements away in the non-confrontational, therapeutic, atmosphere of mediation.

Before receiving legal aid for representation in a divorce case a person is supposed to have a meeting with a mediator to assess whether mediation is a suitable alternative to court proceedings. The only exception to this requirement is in relation to allegations of domestic abuse. However, excluding those exempted for reasons of domestic abuse, only 20 per cent of people publicly funded in divorce proceedings actually get involved in mediation. In March 2007 the National Audit Office (NAO), an independent body responsible for scrutinising public spending on behalf of parliament, published the results of an investigation into this low take-up of mediation in this area. It was entitled Legal aid and mediation for people involved in family breakdown. Its findings were based on an 18-month period, from October 2004 to March 2006, and related to 4,000 people who had received legal aid in relation to marital breakdown proceedings. Those involved were also asked where they had first sought advice and whether their adviser had discussed mediation. Where mediation had been mentioned they were asked why they had either chosen or rejected mediation.

The report confirmed the statistic that only 20 per cent of people funded by legal aid for family breakdown cases presently opt for mediation and further found that:

• 33 per cent of those who did not try mediation said that their adviser had not told them about it. The NAO was particularly concerned at the proportion of legal advisers who failed to tell their clients about mediation, suggesting that the motivation for such failure was financial;

• 42 per cent of those who were not told about mediation would have been willing to try it had they known about it;

• the average cost of legal aid in mediated cases is £752, compared with £1,682 for non-mediated cases. Consequently, if all cases had been mediated the cost to the taxpayer would have been £74 million less and if 14 per cent of the cases that proceeded to court had been resolved through mediation, there would have been resulting savings equivalent to some £10 million a year;

• mediated cases are quicker to resolve, taking on average 110 days, compared with 435 days for non-mediated cases.

In May 2006, the Family Mediation Helpline was officially launched. The Helpline is a public service designed to provide information on, and improve public access to, family mediation.

Its main purpose is to provide information on family mediation and to facilitate referrals to family mediators. The helpline provides: general information on family mediation; more specific information as to whether particular cases may be suitable for mediation and; some information on eligibility for public funding.

The helpline will put callers in touch with mediators in their local area and has a database containing over 600 mediation providers across England and Wales. The helpline number is 0845 60 26 627. There is also a supporting website at www.familymediationhelpline.co.uk. Users of the website can access a service finder, which identifies the mediation services in their local area. It is also possible for users of the website to contact the helpline operators using an online enquiry form.

12.2.3 CONCILIATION

Conciliation takes mediation a step further and gives the mediator the power to suggest grounds for compromise and the possible basis for a conclusive agreement. Both mediation and conciliation have been available in relation to industrial disputes under the auspices of the government-funded ACAS. One of the statutory functions of ACAS is to try to resolve industrial disputes by means of discussion and negotiation or, if the parties agree, the service might take a more active part as arbitrator in relation to a particular dispute.

The essential weakness in the procedures of mediation and conciliation lies in the fact that, although they may lead to the resolution of a dispute, they do not necessarily achieve that end. Where they operate successfully they are excellent methods of dealing with problems, as the parties to the dispute essentially determine their own solutions and feel committed to the outcome. The problem is that they have no binding power and do not always lead to an outcome.

12.3 THE COURTS AND MEDIATION

The increased importance of ADR mechanisms has been signalled in both legislation and court procedures. For example, the Commercial Court issued a practice statement in 1993, stating that it wished to encourage ADR, and followed this in 1996 with a further direction allowing judges to consider whether a case is suitable for ADR at its outset, and to invite the parties to attempt a neutral non-court settlement of their dispute. In cases in the Court of Appeal, the Master of the Rolls now writes to the parties, urging them to consider ADR and asking them for their reasons for declining to use it. Also, as part of the civil justice reforms, the general requirement placed on courts to actively manage cases includes ‘encouraging the parties to use an alternative dispute resolution procedure if the Court considers that to be appropriate and facilitating the use of such procedure’. Rule 26.4 of the Civil Procedure Rules (CPR) 1998 enables judges, either on their own account or at the agreement of both parties, to stop court proceedings where they consider the dispute to be better suited to solution by some alternative procedure, such as arbitration or mediation. CPR 44.3(2) provides that ‘if the court decides to make an order about costs (a) the general rule is that the unsuccessful party will be ordered to pay the costs of the successful party; but (b) the court may make a different order’. CPR 44.3(4) provides that ‘in deciding what order (if any) to make about costs, the court must have regard to all the circumstances, including (a) the conduct of the parties’. Rule 44.3(5) provides that the conduct of the parties includes ‘(a) conduct before, as well as during, the proceedings and in particular the extent to which the parties followed any relevant pre-action protocol’. If, subsequently, a court is of the opinion that an action it has been required to decide could have been settled more effectively through ADR, then under r 44.5 of the CPR, it may penalise the party who insisted on the court hearing by awarding them reduced or no costs should they win the case.

The potential consequences of not abiding by a recommendation to use ADR may be seen in Dunnett v Railtrack plc (2002). When Dunnett won a right to appeal against a previous court decision, the court granting the appeal recommended that the dispute should be put to arbitration. Railtrack, however, refused Dunnett’s offer of arbitration and insisted on the dispute going back to a full court hearing. In the subsequent hearing in the Court of Appeal, Railtrack proved successful. The Court of Appeal, however, held that if a party rejected ADR out of hand when it had been suggested by the court, they would suffer the consequences when costs came to be decided. In the instant case, Railtrack had refused to even contemplate ADR at a stage prior to the costs of the appeal beginning to flow. In his judgment, Brooke LJ set out the modern approach to ADR ([2002] 2 All ER 850 at 853):

Skilled mediators are now able to achieve results satisfactory to both parties in many cases which are quite beyond the power of lawyers and courts to achieve. This court has knowledge of cases where intense feelings have arisen, for instance in relation to clinical negligence claims. But when the parties are brought together on neutral soil with a skilled mediator to help them resolve their differences, it may very well be that the mediator is able to achieve a result by which the parties shake hands at the end and feel that they have gone away having settled the dispute on terms with which they are happy to live. A mediator may be able to provide solutions which are beyond the powers of the court to provide … It is to be hoped that any publicity given to this part of the judgment of the court will draw the attention of lawyers to their duties to further the overriding objective in the way that is set out in Part 1 of the Rules and to the possibility that, if they turn down out of hand the chance of alternative dispute resolution when suggested by the court, as happened on this occasion, they may have to face uncomfortable costs consequence.

The Court of Appeal subsequently applied Dunnett in Leicester Circuits Ltd v Coates Brothers plc (2003) where, although it found for Coates, it did not award it full costs on the grounds that it had withdrawn from a mediation process. The Court of Appeal also dismissed Coates’ claim that there was no realistic prospect of success in the mediation. As Judge LJ stated (para 27):

We do not for one moment assume that the mediation process would have succeeded, but certainly there is a prospect that it would have done if it had been allowed to proceed. That therefore bears on the issue of costs.

It is possible to refuse to engage in mediation without subsequently suffering in the awards of costs. The test, however, is an objective rather than a subjective one, and a difficult one to sustain, as was shown in Hurst v Leeming (2002). Hurst, a solicitor, started legal proceedings against his former partners and instructed Leeming, a barrister, to represent him. When the claim proved unsuccessful, Hurst sued Leeming in professional negligence. When that claim failed, Hurst argued that Leeming should not be awarded costs, as he, Hurst, had offered to mediate the dispute, but Leeming had rejected the offer. Leeming cited five separate justifications for his refusal to mediate. These were:

• the heavy costs he had already incurred in meeting the allegations;

• the seriousness of the allegation made against him;

• the lack of substance in the claim;

• the fact that he had already provided Hurst with a full refutation of his allegation;

• the fact that, given Hurst’s obsessive character, there was no real prospect of a successful outcome to the litigation.

Only the fifth justification was accepted by the court, although even in that case it was emphasised that the conclusion had to be supported by an objective evaluation of the situation. However, in the circumstances, given Hurst’s behaviour and character, the conclusion that mediation would not have resolved the complaint could be sustained objectively.

In Halsey v Milton Keynes General NHS Trust (2004), the Court of Appeal emphasised that the criterion was the reasonableness of the belief.

In the Halsey appeal, the only ground of appeal was that the judge at first instance had been wrong to award the defendant, the Milton Keynes General NHS, its costs, since it had refused a number of invitations by the claimant to mediate. As the court emphasised, in deciding whether to deprive a successful party of some or all of their costs on the grounds that they have refused to agree to ADR, it must be borne in mind that such an order is an exception to the general rule that costs should follow the event. In demonstrating such exceptional circumstances, in the view of the Court of Appeal, the burden is to be placed on the unsuccessful party to the substantive action to show why there should be any departure from that general rule. Lord Justice Dyson said (para 28):

It seems to us that a fair … balance is struck if the burden is placed on the unsuccessful party to show that there was a reasonable prospect that mediation would have been successful. This is not an unduly onerous burden to discharge: he does not have to prove that a mediation would in fact have succeeded. It is significantly easier for the unsuccessful party to prove that there was a reasonable prospect that a mediation would have succeeded than for the successful party to prove the contrary.

In taking such a stance, the Court of Appeal was sensitive to the possibility, as it implicitly suggested was the case in relation to the claimants in the Halsey case, that (para 18):

… there would be considerable scope for a claimant to use the threat of costs sanctions to extract a settlement from the defendant even where the claim is without merit. Courts should be particularly astute to this danger. Large organisations, especially public bodies, are vulnerable to pressure from claimants who, having weak cases, invite mediation as a tactical ploy. They calculate that such a defendant may at least make a nuisance-value offer to buy off the cost of a mediation and the risk of being penalised in costs for refusing a mediation even if ultimately successful …

As regards the power of the courts to order mediation, the Court of Appeal declined to accept such a proposition, finding it to be contrary to both domestic and ECHR law. As Dyson LJ stated in delivering the decision of the Court (para 9):

We heard argument on the question whether the court has power to order parties to submit their disputes to mediation against their will. It is one thing to encourage the parties to agree to mediation, even to encourage them in the strongest terms. It is another to order them to do so. It seems to us that to oblige truly unwilling parties to refer their disputes to mediation would be to impose an unacceptable obstruction on their right of access to the court. The court in Strasbourg has said in relation to article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights that the right of access to a court may be waived, for example by means of an arbitration agreement, but such waiver should be subjected to ‘particularly careful review’ to ensure that the claimant is not subject to ‘constraint … If that is the approach of the ECtHR to an agreement to arbitrate, it seems to us likely that compulsion of ADR would be regarded as an unacceptable constraint on the right of access to the court and, therefore, a violation of article 6.

For a recent example of the courts’ approach, see the Court of Appeals decision in Rolf v De Guerin.

In May 2007, the Ministry for Justice published the results of a research project conducted by Professor Dame Hazel Genn and colleagues. The report, entitled ‘Twisting arms: court referred and court linked mediation under judicial pressure’ related to two pilot mediation schemes operated at the Central London County Court (CLCC). The first scheme involved Automatic Referral to Mediation (ARM). This was a quasi-compulsory mediation scheme that was operated between April 2004 and March 2005 and under it 100 cases each month were randomly selected for referral to mediation. The original intention was that if either or both of the parties involved in the dispute objected to the mediation, they would have had to justify their reluctance to a judge, who would have the power to override their objections if they felt that the case was suitable for mediation. However, following the Halsey decision the scheme had to be altered to allow potential participants to opt out of the scheme. The second scheme considered was the voluntary mediation scheme (VOL), which had been operating in the court since 1996.

In relation to the ARM scheme the research found that:

• by the end of the evaluation (10 months after termination of the pilot), only 22 per cent of ARM cases had a mediation appointment booked and only 14 per cent of those originally referred had actually been mediated;

• there was a high rate of objection to automatic referral throughout the pilot. In 81 per cent of cases, one or both parties objected to being referred to mediation;

• defendants were more likely than claimants to object to referral in both personal injury (PI) and non-PI cases;

• objections to ARM were raised more often in PI cases than non-PI cases;

• the settlement rate over the course of the year was 55 per cent where neither party objected to mediation, but only 48 per cent where the parties were persuaded to attend having both originally objected to the referral;

• when parties were called on to explain their objections to a judge, judicial pressure was unlikely to persuade them to mediate;

• the majority of cases in the ARM scheme settled out of court anyway, without going to mediation;

• in cases where mediation took place, but which did not settle at mediation, parties found that they added £1,000–£2,000 to their costs;

• parties who settled during mediation were generally positive about the process whereas parties who failed to settle during mediation were negative;

• judicial time spent on mediated cases was lower, but administrative time was higher;

• there were no obvious factors in predicting whether or not a case would settle.

As regards the voluntary VOL scheme the research reported an increase in demand following Dunnett v Railtrack. However, personal injury cases continued to avoid the scheme, accounting for only 40 of over 1,000 cases mediated between 1999 and 2004. Despite the increase in the uptake of the VOL scheme, the settlement rate at mediation actually declined from the high of 62 per cent in 1998 to below 40 per cent in 2000 and 2003. Since 1998, the settlement rate has not exceeded 50 per cent.

As for users’ experiences of the VOL scheme, one in four respondents cited court direction, judicial encouragement, or fear of costs penalties as the principal reason for mediating. However, those involved were generally positive about their mediation experience, displaying confidence in mediators and their neutrality. The informality of the process was valued as was the opportunity to be fully involved in the settlement of the dispute. While it was generally felt that successful mediation had saved costs and time, about half of those involved in unsuccessful mediations thought that legal costs had been increased. The most common complaints related to failure to settle, rushed mediation, facilities at the court, and poor skills on the part of the mediator.

In stating what could be learned from the research the report concluded:

• Information from both the ARM and VOL schemes suggests that the motivation and willingness of parties to negotiate and compromise is critical to the success of mediation. Facilitation and encouragement together with selective and appropriate pressure are likely to be more effective and possibly more efficient than blanket coercion to mediate.

• Given the persistent rejection of mediation in personal injury cases, a question arises about the value of investing resources in attempting to reverse this entrenched approach. The lack of interest in mediation on the part of defendant insurance companies is intriguing, given the potential for reducing overall costs through mediation.

• While the legal profession has more knowledge and experience of mediation than was the case a decade ago, it clearly remains to be convinced that mediation is an obvious approach to dispute resolution.

• There is a policy challenge in reaching out to litigants so that consumer demand for mediation can develop and grow. Courts wanting to encourage mediation must find imaginative ways of communicating directly with disputing parties.

• The evaluation of the ARM and VOL schemes, together with recent evaluations from Birmingham and Exeter, establish the importance of efficient and dedicated administrative support to the success of court-based mediation schemes, and the need to create an environment conducive to settlement.

• Where there is no bottom-up demand for mediation, demand can be created by means of education, encouragement, facilitation, and pressure accompanied by sanctions, or incentives. The evidence of this report suggests that an effective mediation–promotion policy might combine education and encouragement through communication of information to parties involved in litigation; facilitation through the provision of efficient administration and good quality mediation facilities; and well-targeted direction in individual and appropriate cases by trained judiciary, involving some assessment of contraindications for a positive outcome. A critical policy challenge is to identify and articulate the incentives for legal advisers to embrace mediation on behalf of their clients.

The above findings assume additional significance in the light of the Justice Ministry’s proposals to reduce the availability of legal aid for litigation in favour of mediation.

A Case Study in How Not to Do It: Burchell v Bullard [2005] EWCA Civ 358

This unfortunate case, for everyone apart perhaps for the lawyers engaged to pursue it, can be taken as a signal example of the dangers and inappropriateness of pursuing legal action in the courts when ADR is available and a better way of deciding the contended issue.

The appellant in the case was a builder who had contracted to build two large extensions on to the defendants’ home. The dispute arose because the Bullards claimed that some of the work carried out by Burchell’s subcontractor was substandard. As a result they refused to make a payment, due under the contract, until the allegedly defective work had been rectified. As a result, Burchell left the site. In an attempt to resolve the dispute Burchell suggested that the dispute be referred to mediation, but on the advice of their chartered surveyor the Bullards refused to mediate, claiming that due to the complexity of the issues the case was not appropriate for mediation.

At first instance the judge, District Judge Tennant, was clear that (para 20):

There are faults on both sides … [o]n balance however, I am satisfied that quite apart from the net amount actually recovered by the claimant, the defendants are more at fault than the claimant in the sense that they have conducted the litigation more unreasonably.

Nonetheless, he decided that each of the parties should pay the costs of the other in relation to the main claim in the action. Burchell subsequently appealed against those costs orders.

The attitude of the Court of Appeal is scathingly evident in the judgment of Ward LJ. As to the offer of mediation he stated that (para 3):

[Burchell’s] solicitors wrote sensibly suggesting that to avoid litigation the matter be referred for alternate dispute resolution through ‘a qualified construction mediator’. The sorry response from the respondents’ chartered building surveyor was that ‘the matters complained of are technically complex and as such mediation is not an appropriate route to settle matters’. (Emphasis added.)

However, as Ward LJ pointed out, ‘All the Bullards wanted was for the builder to complete the contract and rectify the defective work.’ So what was the underlying ‘technically complex’ issue that prevented mediation?

As Ward LJ examined the facts of the case he found things, regrettably but not unexpectedly, getting worse (para 23):

As we had expected, an horrific picture emerges. In this comparatively small case where ultimately only about £5,000 will pass from defendants to claimant, the claimant will have spent about £65,000 up to the end of the trial and he will also have to pay the subcontractor’s costs of £27,500. We were told that the claimant might recover perhaps only 25 per cent of his trial costs, say £16,000, because most of the contest centred on the counter-claim. The defendants’ costs of trial are estimated at about £70,000 and it was estimated the claimant would have to pay about 85 per cent, i.e. £59,5000. Recovery of £5,000 will have cost him about £136,000. On the other hand the defendants who lost in the sense that they have to pay the claimant £5,000 are only a further £26,500 out of pocket in respect of costs. Then there are the costs of the appeal – £13,500 for the appellant and over £9,000 for the respondents. A judgment of £5,000 will have been procured at a cost to the parties of about £185,000. Is that not horrific? (Emphases added.)

In examining the situation, Ward LJ emphasised the fact that the appellant’s offer to mediate was made long before the action started, and long before the crippling costs had been incurred. The issue to be decided, therefore, was whether the respondents had acted unreasonably in refusing the offer of mediation. While Ward LJ recognised that Halsey v The Milton Keynes General NHS Trust had set out the manner in which such a question should be answered, he declined to follow it in the immediate case. His reasoning was as follows (para 42):

It seems to me, therefore, that the Halsey factors are established in this case and that the court should mark its disapproval of the defendants’ conduct by imposing some costs sanction. Yet I draw back from doing so. This offer was made in May 2001. The defendants rejected the offer on the advice of their surveyor, not of their solicitor. The law had not become as clear and developed as it now is following the succession of judgments from this court of which Halsey and Dunnett v Railtrack plc (Practice Note) [2002] 1 WLR 2434 are prime examples. To be fair to the defendants one must judge the reasonableness of their actions against the background of practice a year earlier than Dunnett. In the light of the knowledge of the times and in the absence of legal advice, I cannot condemn them as having been so unreasonable that a costs sanction should follow many years later.

However, Ward LJ was as emphatic as he was admonitory in his assessment of the present case and his view as to how future cases should be treated. As he put it (paras 41–43):

… a small building dispute is par excellence the kind of dispute which, as the recorder found, lends itself to ADR. Secondly, the merits of the case favoured mediation. The defendants behaved unreasonably in believing, if they did, that their case was so watertight that they need not engage in attempts to settle. They were counterclaiming almost as much to remedy some defective work as they had contracted to pay for the whole of the stipulated work. There was clearly room for give and take. The stated reason for refusing mediation, that the matter was too complex for mediation is plain nonsense. Thirdly, the costs of ADR would have been a drop in the ocean compared with the fortune that has been spent on this litigation. Finally, the way in which the claimant modestly presented his claim and readily admitted many of the defects, allied with the finding that he was transparently honest and more than ready to admit where he was wrong and to shoulder responsibility for it augured well for mediation. The claimant has satisfied me that mediation would have had a reasonable prospect of success. The defendants cannot rely on their own obstinacy to assert that mediation had no reasonable prospect of success … The profession must, however, take no comfort from this conclusion. Halsey has made plain not only the high rate of a successful outcome being achieved by mediation but also its established importance as a track to a just result running parallel with that of the court system. Both have a proper part to play in the administration of justice. The court has given its stamp of approval to mediation and it is now the legal profession which must become fully aware of and acknowledge its value. The profession can no longer with impunity shrug aside reasonable requests to mediate … These defendants have escaped the imposition of a costs sanction in this case but defendants in a like position in the future can expect little sympathy if they blithely battle on regardless of the alternatives. (Emphases added.)

In the final analysis the Court of Appeal directed the defendants to pay 60 per cent of the claimant’s costs of the original claim and counterclaim and related proceedings. However, there was still a sting in the tail for as Ward LJ stated (para 47):

We have not heard argument on the costs of this appeal. In order that more costs are not wasted, I say that my preliminary view is that costs of the appeal should follow the event. The appellant has been successful and as at present advised and having regard to the checklist of relevant considerations set out in CPR 44.3, I can see no justification for his not having the costs of the appeal.

So the Bullards faced even more costs for their failure to take advantage of the earlier offer of mediation. (For another case of money being thrown away in pursuit of a ‘matter of principle’, and perhaps even more scathing comments by Ward LJ, see Egan v Motor Services (Bath) Ltd (2007) in which a claim for about £6,000 damages cost £100,000 in fees.)

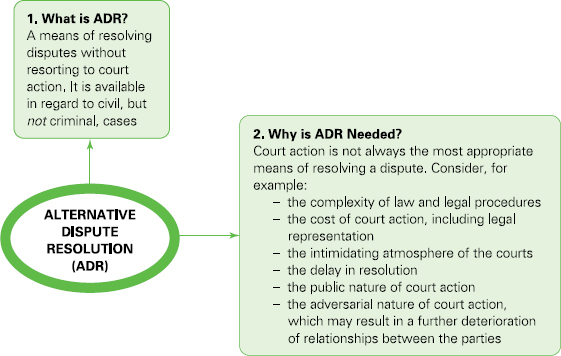

FIGURE 12.1 Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR): an aide-mémoire.

12.4 ARBITRATION

The first and oldest of these alternative procedures to the courts is arbitration. This is the procedure whereby parties in dispute refer the issue to a third party for resolution, rather than taking the case to the ordinary law courts. Studies have shown a reluctance on the part of commercial undertakings to have recourse to the law to resolve their disputes. At first sight, this appears paradoxical. The development of contract law can, to a great extent, be explained as the law’s response to the need for regulation in relation to business activity, yet business declines to make use of its procedures. To some degree, questions of speed and cost explain this peculiar phenomenon, but it can be explained more fully by reference to the introduction to this chapter. It was stated there that informal procedures tend to be most effective where there is a high degree of mutuality and interdependency, and that is precisely the case in most business relationships. Businesses seek to establish and maintain long-term relationships with other concerns. The problem with the law is that the court case tends to terminally rupture such relationships. It is not suggested that, in the final analysis, where the stakes are sufficiently high, recourse will not be had to law, but such action does not represent the first or indeed the preferred option. In contemporary business practice, it is common, if not standard, practice for commercial contracts to contain express clauses referring any future disputes to arbitration. This practice is well established and its legal effectiveness has long been recognised by the law.

Thus in Cable & Wireless Plc v IBM United Kingdom Ltd (2002) the two parties had entered into a contractual agreement which provided that in the event of any dispute they:

shall attempt in good faith to resolve the dispute or claim through an alternative dispute resolution procedure as recommended … by the Centre for Dispute Resolution (‘CEDR’). However an ADR procedure which is being followed shall not prevent any party … from issuing proceedings.

However, when an issue arose the claimant declined to refer its claim to ADR, submitting that clause 41.2 was unenforceable because it lacked certainty due to its apparent contradictory wording, which suggested the possibility of both ADR and the issuing of court proceedings. It was suggested that the clause amounted to no more than an agreement to negotiate, which was not enforceable in English law. However, Colman J held that the issuing of proceedings was not inconsistent with the simultaneous conduct of an ADR procedure or with a mutual intention to have the issue finally decided by the courts only if the ADR procedure failed. He also concluded that the fact that the parties had identified a particular procedure from an experienced dispute resolution service provider indicated that they intended to be bound by the ADR provision. As regards the uncertainty issue, Colman J made a wider reference to the applicability of ADR agreements after Dunnett v Railtrack, holding that the English courts should not go out of their way to find uncertainty, and therefore unenforceability, in the field of ADR references. As he put it, ‘For the courts now to decline to enforce contractual references to ADR on the grounds of intrinsic uncertainty would be to fly in the face of public policy.’

12.4.1 PROCEDURE

Section 1 of the Arbitration Act (AA) 1996 states that it is founded on the following principles:

(a) the object of arbitration is to obtain the fair resolution of disputes by an impartial tribunal without necessary delay or expense;

(b) the parties should be free to agree how their disputes are resolved, subject only to such safeguards as are necessary in the public interest;

(c) in matters governed by this part of the Act, the court should not intervene except as provided by this part.